| MENU SELECTION: | The Italian Campaign | At The Front | Books | Armies | Maps | 85th Division | GI Biographies | Websites |

|

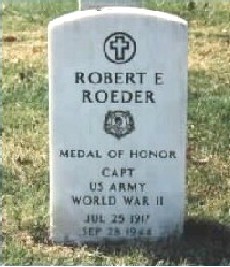

Captain Robert

E. Roeder

Co. G, 350th

Infantry Regiment,

88th

Infantry Division

I wanted to include a biography of a soldier who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. I selected Captain Roeder for several reasons. One is that he was an officer and I thought his story was unique. Also, I've included info on Pfc Felix B. Mestas, Jr., also of Company G, 350th Infantry Regiment and killed in Action on Battle Mountain on 29 September 1944. I am looking for more members of 88th Division.

The 350th Regiment of the 88th "Blue Devils" Division was called the "Battle Mountain Regiment". They earned this name for their stand to hold a 2,345-foot hill in Italy called Monte Battaglia, which the GI's referred to as "Battle Mountain". On Monte Battalglia, the 350th Regiment stood off the enemy from Sept 28 - Oct. 5, although "exposed on three sides, denied air and ground observation, under terrific artillery and mortar barrages, and hampered by bad weather which made supply nearly impossible." A number of officers and men received awards of DSC, Silver Star, and Bronze Star. For its stand there, the 2nd Battalion was awarded the Distinguished Unit Citation. When the British 1st Guards Brigade relieved the 350th Regiment, all officers of Company G had either been killed or wounded and the company was down to only 50 men.Below is the citation that describes how Captain Robert Roeder received the Medal of Honor. I have also included a description of the defense of Monte Battaglia.

Medal Honor Citation Place and date: Mt. Battaglia, Italy, 27-28 September 1944.

Entered service at: Summit Station, Pa. Birth: Summit Station, Pa.

G.O. No.: 31, 17 April 1945.

Born in Summit Station, Pennsylvania on July 25, 1917.

He earned the Medal of Honor while serving in World War II with Company G, 350th Infantry, 88th Infantry Division at Mount Battaglia, Italy. He was killed in action on September 28, 1944 in the action that won him the medal.Citation: for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. Capt. Roeder commanded his company in defense of the strategic Mount Battaglia. Shortly after the company had occupied the hill, the Germans launched the first of a series of determined counterattacks to regain this dominating height. Completely exposed to ceaseless enemy artillery and small-arms fire, Capt. Roeder constantly circulated among his men, encouraging them and directing their defense against the persistent enemy. During the sixth counterattack, the enemy, by using flame throwers and taking advantage of the fog, succeeded in overrunning the position Capt. Roeder led his men in a fierce battle at close quarters, to repulse the attack with heavy losses to the Germans. The following morning, while the company was engaged in repulsing an enemy counterattack in force, Capt. Roeder was seriously wounded and rendered unconscious by shell fragments. He was carried to the company command post, where he regained consciousness. Refusing medical treatment, he insisted on rejoining his men although in a weakened condition, Capt. Roeder dragged himself to the door of the command post and, picking up a rifle, braced himself in a sitting position. He began firing his weapon, shouted words of encouragement, and issued orders to his men. He personally killed 2 Germans before he himself was killed instantly by an exploding shell. Through Capt. Roeder's able and intrepid leadership his men held Mount Battaglia against the aggressive and fanatical enemy attempts to retake this important and strategic height. His valorous performance is exemplary of the fighting spirit of the U.S. Army.

The Defense of Mount Battaglia -- 28 September - 5 October

(Compiled from US Army History series.)

An impressive gain developed when men of Lt. Col. Corhett Williamson's 2d Battalion, 350th Infantry, moved two miles beyond Monte Acuto to Monte Carnavale, there to surprise an enemy company digging in on the reverse slope. Driving the Germans from the mountain, the battalion continued toward Monte Battaglia, a mile and a half to the north-east. Passing the night short of the objective, the men on the next day, the 27th, encountered a group of partisans who claimed to be already in possession of Monte Battaglia. Guided by the partisans along a narrow mule trail, the battalion saw no evidence of the enemy other than sporadic artillery fire.

Reaching Battaglia's crest in mid-afternoon, Colonel Williamson established his command post on the reverse slope. Because he was well in front of the rest of the division, he posted only one company on the summit and deployed the rest to cover a long and tenuous line of communications to the regimental command post. While a few of the partisans remained with the Americans, the others vanished into the mountains, presumably to harass the enemy. From the II Corps commander came the message, "Well done," to which General Kendall and Colonel Fry added their congratulations. Of the high ground in the vicinity of Castel Del Rio, there remained to the enemy only Monte Capello, two miles west of Monte Battaglia.

The surprising ease with which the 2d Battalion, 350th Infantry, had occupied Monte Battaglia quickly proved deceptive. Hardly had Williamson's battalion consolidated its positions than the Germans, supported by mortar and artillery fire, launched two successive counterattacks. By dark both were repulsed, but through the night enemy artillery fire continued to pick at the American positions.

The gains of the past two days had extended the gap between the 350th Infantry and the adjacent unit of the British 1st Division. Dismounted tank crews of the 760th Tank Battalion, which since the 21st had been engaged in covering the II Corps right flank, tried unsuccessfully to close the gap, which by nightfall on the 27th had grown to almost 5 miles. To close it and assure the integrity of the 350th Infantry's supply lines, General Keyes had to draw upon two armored infantry battalions of the 1st Armored Division's CCA, made available from the Fifth Army reserve.

However vulnerable the open flank, the Germans were unable to take advantage of it. Except for Monte Capello; the Americans at that point held all the dominating heights around the Castel del Rio road junction, and from Monte Battaglia northward the ground descended as the Santerno threaded its way to the Po Valley. In the German rear, partisan units, such as the one that had led the way to Monte Battaglia, increased the tempo of their harassment with each passing day, briefly knocking out communications between the parachute corps and Fourteenth Army headquarters. Everything seemed to favor the notion that the admittedly diversionary operation might produce an Allied breakthrough to the Po Valley, a view widely held at Clark's headquarters.

Meanwhile, the main effort of the II Corps had made gratifying, though less dramatic, progress. There the 34th, 85th, and 91st Divisions had gained an average of six miles to close with the high ground flanking the Radicosa Pass. To the east of the II Corps sector, the British 13 Corps' 1st Division, 8th Indian Division, and British 6th Armoured Division, all echeloned to the southeast of the II Corps, pressed on at a somewhat slower pace toward Castel Bolognese and Faenza, four and nine miles respectively southeast of Imola.

Like the Eighth Army, the Fifth Army seemed again to he on the threshold of a breakthrough, but the change in the weather that had brought the Eighth Army to a halt was to have a similar effect on the Fifth Army. For several days, rain and fog grounded virtually all Allied aircraft, especially the ubiquitous artillery spotter planes, and sharply limited the effectiveness of Allied artillery fire. The I Parachute Corps and Fourteenth Army commanders, as had their colleagues on the Adriatic flank, quickly took advantage of the fortuitous break in the weather to reinforce their front.

With a battalion each atop Monte Carnevale and Monte Battaglia, or "Battle Mountain" as the troops called it, Colonel Fry's 350th Infantry remained slightly ahead of the rest of the 88th Division. To the left, about a mile beyond Castel del Rio, Colonel Champeny's 351st Infantry had been stalled for several days, and for the next two would try in vain to drive the Germans from Monte Capello, two miles north-east of the road junction. Farther to the left, a mile west of Castel del Rio, Colonel Crawford's 349th Infantry had no more success in its efforts to push forward.

To Colonel Fry the 2,345-foot Monte Battaglia seemed at first an excellent position; its northwestern slopes and those of a northeastward extending spur, the directions from which the enemy might be expected to counterattack, were quite steep. Yet there were some disturbing features. Deeply indented by ravines and gullies, a grass-covered eastern slope seemed to invite the infiltration tactics at which the enemy was so adept. Monte Battaglia's treeless summit offered little cover or concealment; holes and trenches hacked out of the thin soil and an ancient ruin afforded the only shelter from either the elements or enemy fire. Almost from the moment of arrival on the summit, Colonel Williamson's men had spent their time between enemy artillery barrages and counterattacks in digging dugouts and fire trenches. Each passing hour made it clearer to Colonel Fry how difficult Monte Battaglia might prove to hold. Well ahead of the other regiments and leading the remaining battalions of the 350th Infantry, the 2d Battalion was exposed to fire from three sides. Supplies and reinforcements could reach the men only over the narrow mule trail along a steep-sided ridge connecting Monte Battaglia and Monte Carnevale. To insure use of that trail, Colonel Fry had to deploy his other two battalions along it, enabling the 2d Battalion to concentrate on the summit. This left him little with which to reinforce if the 2d Battalion got into trouble. Rain and fog closing in on the high ground increased the likelihood of enemy infiltration and made footing on the steep trail doubly hazardous.

Hardly had Colonel Fry on 28 September completed moving his command post forward - to within 400 yards of Monte Battaglia - when a message from Colonel Williamson atop Monte Battaglia told of a "terrific counterattack" and a situation that was "desperate." It was the work of troops of the 44th Reichsgrenadier Divsion, [Hoch und Deutschmeister], a competent unit composed largely of Austrian levies. Supported by intense concentrations of artillery fire, the grenadiers struck in approximately regimental strength from three directions. The worst of it appeared to hit Company G, whose commander, Capt. Robert E. Roeder, led his men in a desperate hand-to-hand struggle against Germans swarming over the positions. When Roeder fell, seriously wounded, his men carried him to his command post in the shelter of the ancient ruin. After allowing an aid man to dress his wounds, Captain Roeder dragged himself to the entrance of the old building. Bracing himself in a sitting position, he picked up a rifle from a nearby fallen soldier and opened fire on attacking Germans closing in on his position. He killed two Germans before a fragment from a mortar shell cut him down. Encouraged by their captain's example, the men of Company G rallied to drive the enemy off the summit and back down Monte Battaglia's slopes.

With reinforcement from a company of another battalion sent forward by Colonel Fry, the 2d Battalion by 1700 had beaten back the counterattack, but throughout the night German artillery fired intermittently on Colonel Williamson's positions. Although painful to the men undergoing it, the fire could in no way compare with that put out by American guns. The number of enemy rounds falling on Monte Battaglia rarely exceeded 200 a day or a maximum of 400 rounds for the entire regimental sector. On the other hand, on 1 October, when clear skies permitted artillery spotter aircraft to fly, the 339th Field Artillery Battalion alone fired 3,398 rounds.

Fighting erupted again on Monte Battaglia on 30 September, when Germans carrying flame throwers and pole charges with which to burn and blast paths through the American defenses again stormed up the mountain. For a second time they penetrated the 2d Battalion's perimeter and briefly occupied the ruins of the summit, but as before, Williamson's men rallied to drive the enemy back down the mountain. By that time the position of the men on Monte Battaglia had improved through achievements of adjacent units. On the 30th, the 351st Infantry at last captured nearby Monte Capello, and elements of the British 1st Division came up on the 88th Division's right flank.

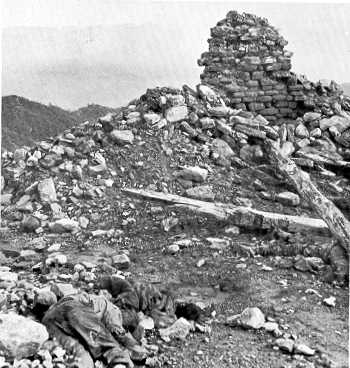

A view of Monte Battaglia's peak and slopes that were defended

by the 2nd Battalion of 350th Regiment.

This photo was taken in 2001 and shows the castle ruins

on the summit and a paved road at the left.

Despite the 88th Division's improved position, the thrust represented nothing more than a narrow salient achieved at considerable cost. Still, if General Clark should choose to pour in fresh troops to expand the salient into a breakthrough to Imola and Highway 9, it could pose a genuine threat to the Germans. Nevertheless, the Fifth Army commander still saw the Firenzuola-Imola road as incapable of carrying the increased traffic reinforcements would generate. Nor had the thrust shown any indications of softening resistance in front of the Eighty Army, at that point apparently checked by determined German defenders in the vicinity of Faenza. In view of that situation and the limited capability of the single road, General Clark had no desire to divert strength from his main effort. What he apparently did not know was that the German command was unable to afford more troops to throw against the salient, and those that had been doing the fighting were close to collapse.

The 88th Division having run into what appeared to be serious opposition and reinforcements having been ruled out, General Clark abandoned the secondary drive on Imola. He now took steps aimed at eventual shift of the left flank of General Kirkman's 13 Corps westward to take over the Santerno valley sector and enable General Keyes to concentrate on the capture of Bologna.

Meanwhile, Colonel Fry had received word that relief for his men on Monte Battaglia was on the way. If all went well, the British might be able to begin replacing the 350th Infantry the following night. The promise of relief had come none too soon for the 2nd Battalion: all officers of Company G had either been killed or wounded and the company was down to only fifty men; Companies E and F were in little better shape.

Although relief was in sight, the 2d Battalion's ordeal was yet to end. Early on 1 October enemy artillery again began falling on Monte Battaglia. After twenty minutes the artillery lifted, and out of the semidarkness the Germans once again attacked up fog-shrouded slopes. This time, however, the sun soon burned off the fog, and a clear sky enabled artillery spotter planes to take to the air to direct defensive fires. With that support the 2d Battalion by midday was able to repel the counterattack and send some 40 enemy prisoners rearward. Shortly after midday officers from the Welsh Guards (1st Guards Brigade) arrived at Colonel Fry's command post to make a reconnaissance before relieving the 350th Infantry.

With the arrival of the British advance party, the defenders of Monte Battaglia had reason to expect they would be off the mountain within twenty-four hours, but that was not to be. Despite aerial bombardment and counter-battery fire, enemy artillery continued to shell the summit, seriously interfering with movement of incoming troops of the 1st Guards Brigade. Three days would pass before the relief was completed and the last of the Americans trudged wearily down the trail from Monte Battaglia.

Since General Kendall's division had re-entered the line on 21 September until the last man left on 5 October, the 88th Division's three regiments incurred 2,105 casualties. That was almost as many as the entire II Corps had sustained during the six-day break-through offensive against Il Giogo Pass and the Gothic Line.

Soon afterwards, the German 98th Division replaced the 44th Reichgrenadier Division. The Allied offense did not penetrate the German defense and gain entry into the Po Valley. It would be another winter before the Allies could build up their strength to launch a Spring Offense that would capture Bologna and route the Germans out of their mountain defenses.

The castle ruins on Monte Battaglia after the stand by Company G. American dead still lies in the foreground. |

Pfc Felix B. Mestas, Jr.

Co. G, 350th Infantry Regiment

Killed in Action on Battle Mountain on 29 September 1944.

For more details about Pfc Mestas and the 350th Regiment, go to Mt. Mestas. [EXTERNAL LINK]

In this photo, Felix is shown wearing the uniform of the 71st Division, prior to his transfer to the 88th Division.

Another soldier who gave his life on Battle Mountain was Pfc Felix B. Mestas, Jr. from La Veta, Colorado. Pfc Mestas and Company G were holding the most forward position in the entire Italian front. After two days, their ammo was running low and they knew that they could not hold off another attack.

On the third day, the Germans attacked Company G with a regiment strenght. As Sgt. Peek recalled, Pfc Mestas stood up in open position to get a better view of the attacking Germans and with his Browning Automatic Rifle slung off his hip, he laid down enough fire cover for the three remaining members of his unit to escape. He killed twenty-four Germans with his BAR and another two with grenades before he died at his position.

Story and photo used by permission of Gary Smith; the webmaster of Mt. Mestas - La Veta, Colorado, at http://www.mtmestas.com. Gary is the nephew of Pfc. Felix Mestas, Jr.

Return to The Greatest Generation biographies Main Menu.

Return to Photos from Italy top menu.

Return to History of Italian Campaign top menu.

Return to CusterMen top menu, about the 85th "Custer" Division.