| INTRODUCTION

In these pages is the battle record of the 100th

Infantry Battalion and the 442d

Regimental Combat Team, units of the Army

of the United States made up of Americans of Japanese ancestry. This is

the story of their part in the battle against the armies of the Third Reich,

“destined to last a thousand years.” Their missions led them from the beaches

of Salerno all the long way up the boot of Italy, then to the deep, shell-scarred

forests of the Vosges in Eastern France and to the treeless barren crags

of the Alpes Maritimes of Southern France. Finally, they were called back

to Italy to fire the opening gun in the last great push that saw the Allied

armies pour through the valley of the Po in a flood that brought an empire

crashing at their feet.

Although it will not again be mentioned in this history, this is also the

climax of the Nisei’s battle against suspicion, intolerance, and a hatred

that was conceived in some dark corner of the American mind and born in

the flames that swept Pearl Harbor.

Let it also be understood that this is not a statement of the contribution

of America’s Japanese-Americans to her war effort. Nisei have fought in

every theatre of war, against the Axis enemy and against the Japanese.

This volume

proposes only to trace the course of two great infantry units, later to

become one, together with their supporting artillery and engineers. Many

stories circulated by overenthusiastic correspondents have given rise to

a popular hctiori that these were supermen. They were not. They could die

and be wounded as easily as other men, and were. They had the same weaknesses

and shortcomings that other soldiers were heir to. Above all, however,

they had the fire, the courage, and the will to press forward that make

crack infantry of the line. They would, and often did, drive until they

fell from wounds or exhaustion; they were never driven to a backward step

in many months of battle against an enemy who counterattacked skillfully

and often. More than one commander acclaimed them as the finest assault

troops he had ever led.

Section

I

ACTIVATION

and TRAINING

Hawaii had been the first territory of the United States to feel the violence

of war when Pearl Harbor and a great part of the Pacific Fleet went up

in flames. Therefore, it seems only fitting that the first Japanese-American

unit was organized in Hawaii, made up of Hawaiian residents of Japanese

extraction. The activation of the Hawaiian

Provisional Battalion took place 5 June

1942. Its soldiers came from the many units which had made up the Hawaiian

National Guard. Lieutenant Colonel Farrant L. Turner, former executive

othcer of the 298th Infantry, took command. The day that the official

activation took place, the battalion sailed from Honolulu Harbor. One week

later the ship docked at San Francisco, and the same day, 12 June 1942,

the unit was redesignated the 100th Infantry

Battalion (Separate).

The battalion took its basic training at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, moving

to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, January 1943 for advanced training and maneuvers.

Here the unit first trained with the 85th

Division, whom they were to meet again

under different circumstances in the Italian campaign.

Shortly thereafter, the War Department, continuing its policy of permitting

the Japanese-Americans to bear arms in defense of their country, activated

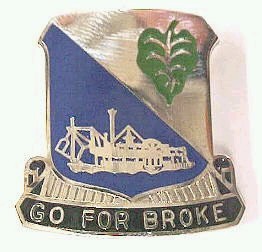

the 442d Regimental Combat Team on 1 February 1943. This unit was composed

of the 442d Infantry Regiment; the 522d Field Artillery Battalion; and

the 232d Combat Engineer Company. Colonel Charles W. Pence was the Combat

Team commander.

Consequently, when the 100th Battalion returned from maneuvers 15 June,

they found the 442d Combat Team with its complete complement of men and

material, well into its training program. There was time to renew old friendships.

These were many, since most of the troops of the 442d at this time were

volunteers from the Territory of Hawaii, although the cadre had come from

Nisei then in the Seventh Service Command.

Two months later, ii August 1943, the 100th Battalion left Camp Shelby,

staged at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, and departed via the New York Port of

Embarkation. One battalion was on the way.

The 442d Combat Team continued its training until the end of 1943, when

calls for replacements for the tooth Battalion began to come in. The fighting

at Cassino and Anzio had used up its available strength and

more. Men and officers were shipped out, but training went on. From 27

January to 17 February 1944, the Combat Team participated in “D” Series

Maneuvers with the 69th Division

in the DeSoto National Forest, Mississippi. The 522d Field

Artillery Battalion, which had been on maneuvers in Louisiana, returned

to the fold in time to catch the tag end of these problems. As a result

of the excellent showing the unit made, alert orders were soon forthcoming.

Since there were not sufficient men left to fill three battalions after

the calls that had been made on the regiment for replacements, the 2d and

3d Battalions were brought to strength by further draining the 1st Battalion.

Finally, in a haze of waterproofing, crates, shipping lists, and inspections,

the Combat Team, less one infantry battalion, left Camp Shelby 22-2 3 April

1944 for the Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia, staging area. The few officers

and men who were left in the 1st Battalion furnished the cadre for the

171st

Infantry Battalion (Separate) which later

trained most of the replacements for the Combat Team. May Day, 1944, saw

the men filing up the gangplanks at the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation.

On 28 May, the ships docked at Naples Harbor after a long, thoroughly uneventful

voyage.

Section

II

THE 100TH INFANTRY

BATTALION ROAD TO ROME

Fifteen months after the 100th Infantry Battalion had been activated, the

men stepped down the gangplank on an alien shore. The port: Oran, North

Africa. The date: 2 September 1943. One week later, on the 8th, the battalion

was assigned to the already battle-tested 133d Infantry of the 34th Division,

victors at Hill 609 in Tunisia. The battalion took the place of the 2d

Battalion of the i33d, then acting as security guard for Allied Force Headquarters

in Algiers.

Then came the news the world had long been waiting for, the landings on

the beaches of Paestum and Salerno on 9 September 1943. On the 22d, D plus

13, the 133d landed at Salerno beach and began the march inland. Immediately,

the two extra rifle companies (E and F) which the 100th had been authorized

on activation were placed under Fifth Army control to guard airfields and

supply dumps. The employment of these extra companies remained a recurrent

problem all through the campaign until heavy losses absorbed and deactivated

them. After a few days awaiting orders in an assembly area, the 133d, with

it the 100th, took off 27 September in pursuit of the retreating enemy.

Successively, the battalion occupied Montemarano and, after a short,

sharp battle, the important road junction of Chiusano where they set up

a road block. Meanwhile, the 10th German

Army had been slowly withdrawing to the

high ground northwest of Benevento, key road and rail center on the Fifth

Army’s right flank. Quickly, the other

two battalions of the regiment swept ahead and seized the approaches to

Benevento, and the 100th was ordered to move up and support the attack.

Enroute, new orders shifted them to the left of the 3d Battalion which

would assault the town while the 100th swung through to take the heights

to the northwest. After a spectacular twenty-mile forced march, both units

secured their objectives. The only opposition came from harassing artillery

as they slogged through a pouring rain that turned roads into ankle deep

quagmires. Now the 45th Division took up the pursuit, supported by the

133d, until 5 October, when the regiment went into Corps reserve near San

Martino. Casualties had been comparatively light: three men killed, and

two officers and 29 men wounded or injured. On the toth, the iooth, in

division reserve, had moved up in preparation for the first Volturno River

crossing. The initial smash was successful, however, and the division went

across around midnight of the following day in the vicinity of Limatola,

the 100th Battalion still in reserve.

Mid-month found all units steadily moving forward, with the moth in the

vicinity of Bagnoli. In the meantime, the Red

Bull Division {34th}was

making plans for the second crossing of the Volturno on 18 and 19 October.

The 133d was ordered to occupy the central sector of the division layout,

assaulting to secure a bridgehead astride the Dragoni—Alife road. The tooth

would delay its crossing for a few hours to protect the rear of the regiment.

The 1st Battalion made its crossing under a smoke screen the afternoon

of the i8th and the tooth, after cleaning up the remaining pockets on the

south bank, crossed late the following night. They then moved up to the

flats south of Alife, sending patrols out to contact the enemy, the 29th

Panzer Grenadier Regiment, which was defending

behind thick minefields and dug-in machine gun nests. The night of 20 October,

the 100th moved out to seize the road junction 1,000 yards east of St.

Angelo d’Alife. Before the battalion could get into the high ground it

was caught in a murderous fire from the German defense perimeter, backed

up by artillery and the multi-barrelled “screaming meemies,” and casualties

soared. The battalion hung on in the face of the concentrated fire while

the 1st Battalion swung around to the right flank in an attempt to envelop

the resistance. Failing this, the tooth was pulled back to an area that

offered more protection, and remained there for two days while the regiment

was reorganized under a new commander. The morning of the 22d, with the

tooth and 3d Battalions in assault, the regiment renewed the drive on Alife.

A and C Companies advanced slowly across the flats and by dark had driven

half way to their objectives where they halted n the face of intense machine

gun and sniper fire.

Meanwhile, the Germans had brought up a company of tanks to bolster the

sagging defenses. One of these was destroyed at 25-yard range by the battalion’s

tank buster, Private Masao Awakuni, bazooka man extraordinary. The

remainder were driven off by artillery fire. Forty-eight hours after the

jump off, A and C Companies had stormed and seized Alife, where they were

relieved by E and F Companies, who were then ordered to push on and seize

the heights west of Castello d’Alife. By 0900 of the 25th, the 100th

had advanced to within a thousand yards of the crest of “Castle Hill”

and was ordered to dig in there while another battalion swung around on

the enemy’s left rear and drove them back. The action was successful, and

the regiment consolidated, having driven the enemy out of another of his

“strong delaying positions” that characterized his defensive tactics throughout

the Italian campaign. This particular one cost the 100th 21 killed and

66 wounded.

Four days later, 29 October, Lieutenant Colonel Farrant L. Turner,

who had commanded the 100th since the day it was activated, was relieved.

Major (later Lieutenant Colonel) James L. Gillespie took over the

battalion in time to prepare for the third and last crossing of the serpentine

Volturno River. By 1 November, the 133d controlled the high ground near

Giorlano which overlooked the Volturno where the battalion would have to

make its crossing. The enemy, as always, held the high ground on the other

side. At daylight of the ist, the 100th cleared what opposition remained

as far as the river bank, losing 12 casualties to six strafing Messerschmitts

in the process. This, of course, was in the days before the Luftwaffe started

having troubles of its own. The next two days were spent in pre-assault

planning. The night of the 3rd, the attack was mounted with the tooth echeloned

to the left rear of the division so that contact could be maintained with

the 45th Division.

Troop opposition was light, being confined to small arms fire, but the

inevitable mines took a heavy toll as the battalion struggled through the

dark. By 0740 of the 4th, the tooth was astride the railroad 2,000 yards

from the river and making good headway when the enemy defense began to

harden, requiring stiff fighting to dig them out of the battalion sector.

The morning of the 5th, the 1st Battalion was counterattacked and driven

off Hill 550. A coordinated attack was then planned with the 1st Battalion

retaking the hill it had lost while the 100th stormed Hills 590 and 610

on the next ridge line to the northwest. The assault jumped off in daylight

in the face of heavy enemy artillery fire and progressed rapidly, catching

the Germans off guard. Both objectives having been taken, the battalion

rolled on to take Hill 600 near Pozzilli in the face of determined

enemy resistance. The enemy tried desperately to retake these heights with

assaults from the front and flanks, but was consistently driven back, partly

through the efforts of Lieutenant Neill M. Ray and Corporals

Katsushi Tanouye and Bert K. Higashi of D Company’s mortar platoon.

These men remained at an observation post in advance of the line of platoons

and directed mortar fire each time the enemy tried to form for a counterattack

through the morning of the 6th, even though their position was made almost

untenable by constant shelling. They remained at their posts until all

three were killed instantly by a direct hit. At the same time, E and F

Companies had been moved into line to close the gap between the 34th and

the 45th Divisions

on the left, thus cutting down the threat from the flank.

Meanwhile, the 45th Division

had broken through into Venafro and the enemy began another withdrawal,

enabling the battalion to pull back for a short rest on the iith. Casualties

had been heavy: three officers killed and 18 wounded; 75 men killed and

239 wounded; one man missing. These losses, together with the endless rain

and fog and cold, combined to lower the spirits of the men. Then, to cap

the climax, the battalion was recommitted in the vicinity of Colli-Rochetti

the day before Thanksgiving, relieving elements of the 504th

Parachute Regiment. Immediately, the battalion

was ordered to attack the hills to its front to secure a Line of Departure

for the 133d in a general assault which was to take place 1 December. The

34th

had been ordered to attack down the Coli-Atina road, which ran east and

west, and seize the high, difficult terrain around Atino. Such a move would

flank the Liri Valley and force the Germans to abandon their Cassino defenses

where the high command anticipated they would make their winter stand.

Early, the morning of 29 November, the battalion jumped off against Hills

801,

905,

and 920. Resistance was fierce, and the enemy threw artillery, mortar,

and nebeiwerfer in an effort to stall the attack. The riflemen of A, B

and C Companies who had moved up the reverse slopes of all three mountains

hung on grimly, and on the 30th, with the troops moving behind heavy artillery

concentrations, the high ground was taken. There the battalion stayed for

nine days while the other battalions of the regiment tried to push through

on the right and break the stalemate, but to no avail. Finally, 9 December,

the 100th came down from the hills and counted its losses: two officers

and 4 men killed; five officers and 135 men wounded or injured; six men

died of wounds; two men were missing. E and F Companies had both

been disbanded to fill the ranks, but fighting strength remained low. Lieutenant

Colonel Gillespie, the commanding officer, had been lost through illness,

and was replaced temporarily by

Major Alex E. McKenzie, then by

Major

William H. Blytt of the 133d. On the 10th, the 100th went back to Alife,

where they rested and trained until the 30th. In that area,

Major Caspar

Clough, Jr., formerly with the 1st

Division, took over the battalion.

New Year’s Eve of 1944 saw the 100th close into the Presenzano area

under control of the veteran II Corps.

The next few days were spend in reconnaissance to the front and flanks,

preparatory to joining the 1st Special

Service Force near the Radicosa Hills

on the 6th. The night of January, the battalion engaged in an attack on

Hill 1109, one of a series of mountains overlooking Cassino. The objective

was taken against light resistance and held until the iith when the 100th

jumped off against the last barrier, meeting heavy fire from artillery

and mortars as well as from carefully laid out defensive positions. Finally,

the Special Service Force executed a coordinated attack, sending its 1st

Battalion down the ridge while the 100th attacked to the front behind a

thunderous demonstration of fire power. On the 13th, Hill 1270 fell. Two

days later, led by Lieutenant Harry I. Schoenberg’s A Company, the battalion

struck out for San Michele, situated on the bluffs below Hill 1270 and

looking across the valley at Cassino. The town fell by 1930 hours and for

the next six days, after going back to control of the 133d, the battalion

waited for the assault on Cassino, and patrolled to the front and flanks.

At 2330 hours of the 24th, the 133d initiated the first attack against

Cassino by way of the Rapido River. After an hour and twenty minutes’ barrage,

the 100th jumped off with Companies A and C leading, along with elements

of the Ammunition and Pioneer platoon. By the following morning, the two

companies had gained the river wall, and held there to establish a Line

of Departure for an attack across the river. The morning of the 25th, B

Company, which had secured the original Line of Departure, was moved up

to force the river line, but the enemy was not to be fooled twice. The

company was caught in a terrific artillery concentration, and only fourteen

men reached the river. The remainder were killed, wounded, driven back,

or forced to find shelter where they could. Still, the order was to attack.

The commanding officer, Major Clough, was wounded the same day and Major

Dewey of the 133d took command. On the 25th, when Major Dewey went on a

reconnaissance with the executive officer, Major Johnson, and Captain

Mitzuho Fukuda, commanding officer of A Company, the party was caught

by machine gun fire. Major Dewey and Major Johnson were hit, and in trying

to disperse, one of the party tripped a mine which killed Major Johnson.

Its leaders lost, the 100th was pulled back to San Michele. Providentially,

Major

James W. Lovell, the battalion’s original executive officer, returned

from the hospital and took command on 29 January, readying the unit for

an attack on the castle northeast of Cassino, halfway up the mountain to

the famous monastery. The 135th

and 168th

were to attack the monastery and the remaining two battalions of the 133d

were to take Cassino itself from the rear. At 0645, 8 February, the battalion

moved out and advanced rapidly, despite. heavy shelling, until ordered

to hold on Hill 165 and protect the right of the regiment. All other units

had been stopped by fierce resistance. Both flanks of the battalion were

now exposed, and a change in the wind pulled away its smoke screen, exposing

it to direct observation and murderous fire. Grimly, the 100th held for

four days and then withdrew on order, sending B Company into that part

of Cassino that had been taken, and withdrawing the rest of the battalion

to regimental reserve. Major Lovell had again been wounded seriously on

the first day of the attack, and Major Clough returned to command. The

division launched another abortive attack on 18 February sending the 100th

to storm the same objective. Four days later, the battalion pulled back

to Alife for rest and reorganization.

For the 100th Battalion and for the 34th Division, this was the end of

the forty-day struggle against impossible odds, plus the cream of the German

Army. Rest meant relief from the cold, bitter weather that left men chilled

to the bone and swelled their feet to the point where it was torture to

take a step. The ranks were thin, so thin that when the medics carried

a man out now, there was no one to take his place, only a gap in the line

and an empty foxhole where he had been. This was the end of the fighting

in Cassino itself, fighting that was never measured in yards or miles.

It was measured instead, in houses taken, in rooms of houses, and in cells

of the jail wrested from the German paratroopers one by one.

These men had seen all that there was to see, endured all that there was

to endure. They had seen Cassino and the ancient Abbey crumble under the

weight of thousands of tons of bombs and shells. They had attacked, only

to find the German infantry risen from the rubble and the ashes to drive

them back. They had learned that air power was not enough.

The attack on Cassino had failed, that much was clear. But history will

record that when the line was finally broken and the enemy reeled back,

five fresh divisions took on the job that one division so gallantly attempted

and so nearly completed. History will also record that among the foremost

in the ranks of that division were the men of the 100th Infantry Battalion.

Among their ranks were fewer and fewer of the men who had started overseas

with the battalion, because casualties had again been heavy: four officers

and 38 men killed; 15 officers and 130 men wounded or injured; six men

died of wounds; two men missing; and one officer and one man, prisoners.

In the meantime, all was not too well at Anzio. The battle had been long

and decimating; reinforcements were badly needed. So, on 26 March, the

34th

Division landed at Anzio Harbor, with

it the 100th. On 30 March, the 2d Battalion of the 133d

returned, replacing the 100th. Fifth Army, however, left the battalion

with the 34th Division. During this time, replacements from the 442d Combat

Team (the Combat Team was in Camp Shelby and preparing to come overseas)

had come in, bringing the battalion nearly up to strength. Through April

and on into May, the opposing forces fenced and sparred, sending out patrols

and raiding parties for prisoners and information. The German “Anzio Express”

and smaller guns constantly kept the beachhead under fire, causing casualties

and keeping nerves stretched taut.

Finally, on 24 May, 1944, the Anzio beachhead which had smoldered so long,

burst into flame and exploded in the faces of the Germans. Behind tremendous

air and artillery preparations, the race for the Eternal City was on. The

100th Battalion was initially given the mission of protecting the VI

Corps’ right flank along the Mussolini

Canal, with a frontage that eventually reached 14,000 yards. The great

drive rolled on until the 2d of June, when the enemy put up a last ditch

defense around Lanuvia and La Torretto, creating a bulge in the 34th

Division’s line which had to be reduced,

and the battalion was ordered to take on the job. After an intense 36-hour

battle in which the 100th suffered 15 killed, 63 wounded, and one missing,

the line was cracked and the Road to Rome was open. For this single action,

six members of the battalion were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross,

and one, the Silver Star. About noon of 3 June, Lieutenant Colonel

Gordon Singles, who had assumed command of the battalion at the beachhead,

was put in command of a task force. This force crushed the last German

resistance in the sector. The next day the task force began to roll. They

swept through Arricia and Albano, marching, riding when they could on what

they could, until they were ordered to stop eleven kilometers from Rome

while armor took up the chase. At 2200 hours, 5 June 1944, the 100th Battalion

boarded trucks and rolled through Rome, along with the rest of the Red

Bull Division until that outfit was finally

relieved after the capture of the old port of Civitavecchia, many miles

from the Eternal City.

It was there that the 442d Combat Team caught up with the 100th in the

middle of June, having come from Naples through Anzio and Rome. There also

the 100th became the First Battalion of the 442d Combat Team, which was

only fitting, since the original ist Battalion of the 442d had been bled

dry to furnish replacements for the 100th during the long winter campaign.

This was the beginning of an association that was to become famous through

two armies: The 442d Infantry Regiment, the 522d Field Artillery Battalion,

and the 232d Combat Engineer Company.

Section

III

THE 442ND ROME

TO THE COMBAT TEAM ARNO—"AIRBORNE"

{I have no clue as to why "Airborne" is in the title of this section, except

that they served with the 517 PIR.}

Several days after the 100th Battalion had been attached to the 442d Combat

Team, the two merged in a bivouac area a few miles from the port of Civitavecchia.

The Red Bull Division

had been pulled up short for a rest in this area while the 36th

Division took up the chase of the retreating

enemy. Here the troops trained until 21 June, when they entrucked and moved

to another bivouac area southwest of Grosetto. From here, reconnaissance

was instituted and final preparations were made to take the unit into combat.

Five days later, on the 26th, the regiment was committed to action in the

vicinity of Suvereto; the 2d Battalion passed through the 142d

Infantry. The 3d Battalion passed through

the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

The 100th Battalion was being held in reserve. The regimental objective

was a key road junction beyond the town of Sassetta. On the left, the 3d

Battalion advanced slowly, against stiff small arms resistance, although

artillery fire was light. On the right, the 2d Battalion’s advance slowed

and stopped in the face of murderous artillery fire. At this point, around

1200 hours, the 100th was committed, driving through a gap between the

two assault battalions to seize the high ground around Belvedere, and cut

the Suvereto— Sassetta road. Immediately, A and B companies swung northeast

to seize a hill which the Germans had neglected to cover and which overlooked

Belvedere. From here they observed the enemy’s defensive positions, and

several artillery pieces which had been shelling the 2d Battalion. Company

A now launched an attack on Belvedere and Company B swung back to cut the

road south of the town.

This assault on their flanks and rear completely demoralized the enemy,

and the defenders were quickly chopped up in small groups and annihilated

or captured with all their arms and equipment. The bag for the day was

one SS battalion completely destroyed.

The 3d Battalion, continuing the frontal attack, had cleared Suvereto at

1500 hours, and the regiment pushed out along the Suvereto—Sassetta road

in a column of battalions— tooth, 3d, and 2d. For the Belvedere action,

the tooth Battalion was later awarded a Presidential Citation.

The following day, the 100th stormed into Sassetta, while the 3d Battalion

executed a flanking movement and seized the high ground overlooking the

town from the north. The 522d Field Artillery Battalion, Cannon Company,

and the massed mortars and machine guns of the 100th and 3d Battalions

supported the attack, picking off enemy stragglers and nipping one counterattack

in the bud.

Following this breakthrough, the Combat Team, less the 3d Battalion, went

into division reserve near Bibbona to rest for a day or two and meditate

on some of the lessons the new men had learned in their first few days

of battle; lessons that proved valuable in some of the bitter days that

came later. Probably the most important thing the young regiment discovered,

much to everyone’s surprise, was the fact that advice, even from battle-wise

veterans, was well-meaning but practically useless. A well-trained soldier

acquires his final polish in battle, and in no other way. The experience

had proved fatal to some, but to most of the men it had been the best teacher

of all.

Meanwhile, the 3d Battalion had been swung far to the right of the division

sector to block against a possible counterattack from the northeast, where

the 1st Armored Division had

opened a gap between the two divisions. When this threat failed to materialize,

the 3d Battalion rejoined the Combat Team. All three battalions crossed

the Cecina River on i July with the 2d and tooth in assault, and drove

north to cut off an important road junction five miles northeast of Cecina.

The objective was secured after the 522d Field Artillery and the regimental

Cannon Company poured a paralyzing concentration of fire on the German

troops defending there.

The following day, the regiment pushed on to cut the east-west road from

Castellina to the sea. Here, however, the enemy elected to put up his most

determined stand since his defenses before Rome, and the attackers ran

into a storm of fire of all types. Our troops were limited to small gains

for the next two days, though they kept up a steady pressure against the

enemy.

On 4 July, the 3d Battalion moved in to relieve the 100th; the 2d and 3d

Battalions went on to grind out a costly yard by yard advance against Hill

140 and the ridge line running west from it to the coastal plain. By the

afternoon of the 5th, the 3d Battalion had overrun strong enemy defenses

dug into the caves, and the 2d Battalion, after two days of butting into

the enemy’s interlocking fires on a hillside that contained little cover

and no concealment, stormed and seized their part of Hill 140 in a vicious

night attack before dawn of6July. Enemy casualties on the positions overrun

by the regiment approximated 250.

Here the 100th Battalion swung around the right flank of the 2d, and driving

abreast of the 3d, cut the Castellina road and cleared Castellina by the

evening of the 7th. Still the enemy gave ground grudgingly, and it became

evident that here in these hills and not in the port itself would the battle

of Leghorn be fought. Accordingly, the regiment settled down to its task

and battled the enemy where he chose to stand, seeking to destroy his defenses.

The 2d Battalion relieved the 3d on the 10th of July, and the 100th and

2d again jumped off abreast with the mission of clearing the hilltop town

of Pieve di San Luce. They had advanced only a short distance when they

were stopped decisively by heavy fire from their objective and from Pastina,

which lay in the hills to the right front of the 100th. Immediately the

100th took to the high ground to clear Pastina, while the 2d Battalion

dug in in the valley below and hung on against all the artillery the enemy

could muster. After a two-day battle, Pastina fell at 2300 hours 12 July

to the combined efforts of the 100th and deadly spot shooting by the 522d

Field Artillery Battalion.

Here the 3d Battalion took over again from the 100th and drove north, abreast

of the 2d Battalion, as far as Lorenzano, where the advance spluttered

and ground to a halt against one of the enemy’s inevitable hill positions.

On 14 July the 168th Infantry

relieved the 3d Battalion in front of Lorenzano, leaving that battalion

free to swing back to the left of the sector and replace the 2d Battalion

on the night of the 15th. In the meantime, the 100th Battalion had passed

to division control and was driving northwest on the Orciano—Leghorn road,

establishing a series of roadblocks to protect the left flank of the regiment

and at the same time to threaten the city of Leghorn itself.

The 3d Battalion, 442d, having relieved the 2d Battalion, drove north for

the little hilltop town of Luciano, which controlled the roadnet around

Leghorn. At Luciano, the enemy had chosen to make his stand. All through

the 16th and 17th, the battle for the town raged. The 522d and other elements

of division artillery poured thousands of rounds into the defenders’ positions.

The 232d Engineer Company, with assistance from the division engineers,

worked under small arms fire to clear mines so that the ammunition and

supplies could come up. The 2d Battalion had moved up the ridge to the

left and rear of Luciano, clearing enemy positions there, and covering

that flank. Luciano fell the night of the 17th, and the following day,

the 3d Battalion swept on, liberated Colle Salvetti, and occupied the last

high ground south of the Arno River. Observation Posts could see the famed

Leaning Tower of Pisa in the distance. The same day, Leghorn was entered

with little opposition by elements of the 91st Division, followed by the

100th Battalion, 442d.

Both the 2d

and 3d Battalions now pushed cautiously out, finally setting up an Outpost

Line of Resistance along Highway 67 on the 20th of July, while the 100th

occupied and policed Leghorn. One patrol from the 3d Battalion penetrated

the southern outskirts of Pisa the night of the 20th and returned 36 hours

later with a great deal of valuable information on defenses in the city.

On the 22d, the regiment, less the 100th, was relieved and closed into

an assembly area near Colle Salvetti; from there, it moved to a division

rest area around Vada on the 24th, being joined by the 100th the next day.

In this area the 100th Battalion (Separate) was redesignated as the 100th

Battalion, 442d Infantry Regiment, effective in August 1944, and was reorganized

as such.

After a long, pleasant rest. together with some training around Vada, the

Combat Team was detached from the 34th

Division and assigned to IV Corps. The

100th Battalion was sent to take up a line along the Arno River four kilometers

east of Pisa, while the remainder of the 442d Combat Team moved into the

85th Division sector near Castelnuovo, 17th August, only to be detached

the following day and sent to the veteran II Corps’ 88th

Division. On the 20th, the 2d and 3d Battalions

moved into line along the Arno near Scandicci, immediately west of Florence.

Now began a period of intensive patrolling and much activity. Reconnaissance

patrols probed the enemy’s positions day and night, while night raiding

parties forded the Arno River to take prisoners and gain information on

the enemy’s dispositions. The purpose of all this activity was to give

the Germans an impression of great strength and to screen major troops

movements elsewhere on the Army front. This fencing and probing continued

until 1 September, when the entire Fifth Army front exploded into action.

The drive for the Gothic Line had begun. The 2d and 3d Battalions forced

a crossing of the Arno in this sector, pushing north astride Highway 66.

Many miles to the west, the 100th Battalion also forced a crossing in the

Pisa sector. All elements were relieved shortly thereafter, and subsequently

assembled at Rosignano. Later the regiment less its vehicles embarked at

Piombino for Naples to begin the first leg of the journey to France. On

the 26th of September, the men of the Combat Team boarded Coast Guard troop

transports in the Bay of Naples and turned their faces toward the French

shores and the Seventh Army.

-----------o-----------

The Anti-Tank Company was detached from the Combat Team 15 July 1944 and

ordered to join the 1st Airborne Provisional

Division (later the ist Airborne Task

Force) south of Rome. This was effected and the company was reorganized

for glider operations. Training began 28 July and lasted until 14 August,

D-1, for the strike at Southern France. Fifteen August, the gliders carrying

Anti-Tank Company, newly equipped with jeeps and British six-pounders,

took off. Landing was effected on the French coast around Le Muy, and the

troops took up blocking positions to protect the paratroops who had landed

ahead of them. Here they remained until the 17th when troops of the 45th

and 36th Division

broke through from the beach to relieve them. {D-1

means they trained up until one day prior to D-Day.}

Still supporting the 517th Parachute Infantry{Regiment},

the company then took part in the drive toward the Franco-Italian border,

jumping off from Le Muy, 18 August. The drive continued against scattered

enemy resistance until the force ran into strong defensive positions around

Col du Braus, overlooking the border town of Sospel. This was reduced by

early September. On 11 October, Anti-Tank Company was detached from the

517th,

given a rest, and sent back to rejoin the Combat Team The company returned

to regimental control 26 October 1944, in time to assist in the battle

to relieve the “lost battalion.”

The

442RCT was transferred to the 7th Army serving in on a second front in

Southern France that was linking up with the US and British armies that

landed at Normandy.

Section

IV

THE BATTLE

OF BRUYERES - "LOST BATTALION",

"THE CHAMPAGNE

CAMPAIGN"

The

Following Text is omitted ---- Not related to Ialian Campaign

The 442RCT was assigned to the 36th "Texas"

Divison. The 442nd earned more honors and casualties in forcing a

relief of the 1st Battalion of the 141st Regiment, 36th Divison, that was

surrounded and isolated. On 30 October, 1944, the 442RCT made contact

with this "Lost Battalion". The 442nd unit lost more than 800 troops

while recuing 211 men behind enemy lines.

During four months of winter, the 442RCT

occupied the Italian-Franco border area north and east of Nice. The

coastal resort area allowed some time for rest and relaxation. On

March 17th, they were marched out to load LSTs to return to Italy.

The 522 Field

Artillery Battalion was reassigned to 7th Army. |

Text

picks up in Spring of 1945, near end of war.

[1945]

Section V

RETURN TO ITALY—MASSA

TO GENOA END OF THE WEHRMACHT

Debarking at Leghorn, which it had fought for many months before,

the Combat Team moved to a Peninsular Base Section staging area near Pisa,

and drew entirely new equipment. It then moved, under control of IV Corps,

to an assembly area at San Martino, near Lucca. Finally, on 3 April,

the Combat Team was detached from Corps, assigned direct to the Fifth Army,

and attached to the 92d Division

for operations. General Almond assigned the Combat Team the sector from

Highway One east to include the Folgorito ridge line, a 3,000-foot hill

mass which rose abruptly from the coastal plain, dominating Massa, Carrarra,

and the great naval base of La Spezia.

The mission of the 92d Division

with the 442d

and 473d Infantry Regiments

attached was to launch an offensive some time before the main weight of

the Fifth Army was hurled at Bologna. It was believed that such

a move would lead the enemy to divert some of his central reserve, then

massed in the Po behind Bologna, to meet this threat to his flank.

{473rd Infantry Regiment was formed from several anti-aircraft units that

were no longer needed because the German air force was no longer a threat.

They were attached to the 92nd Division serving on the west coast of Italy.

At this time the 92nd Division was made up of 3 races: Caucasian, Black

& Japanese(Nisei).}

Under cover of darkness 3 April {1945},

the 100th Battalion moved into a forward assembly area in the vicinity

of Vallecchia. The 3d Battalion detrucked at Pietrasanta, and marched eight

miles over mountain trails to Azzano, a mountain village which was under

full enemy observation during daylight. There the unit remained hidden

until the next night, when it moved out, led by a Partisan

guide, and gained the ridge line between Mount Folgorito and Mount Carchio.

This move had been a long gamble on the part of Colonel Miller, the regimental

commander. It was necessary that the troops achieve this ridge line without

detection since it was a Herculean task in itself merely to scale the sheer

mountain walls. It would have been an impossibility to take the position

by storm. Success meant that a position which had resisted the 92d

Division for six months would probably

fall in two days. Failure meant that the regiment would be forced to make

a costly frontal attack on these same positions. Our troops did not fail.

Gaining the ridge line, the 3d Battalion jumped off at 050500 April, enveloping

the enemy from the rear. At the same time, the 100th Battalion attacked

the enemy positions on the ridge line which ran southwest from Mount Folgorito

to the coastal plain. {050500 = date &

hour or 5am on 5th}

The attacking battalions, having moved toward each other for 24 hours,

made contact on Mount Cerretta late the following day. They had

been supported by three battalions of artillery plus a very effective air

strike, and enemy casualties were extremely heavy. Exploiting the initial

advantage, the 2d Battalion had followed the route of the 3d during the

night of 5 April, and at 061000 swung north from Mount Folgorito to seize

Mount Belvedere. This was a long mountain top, having a knoll at each corner

and forming a rough rectangle. Resistance was heavy and the mountain was

not occupied by nightfall.

On the 7th, the 100th consolidated its gains, while the 3d made an attack

on the Colle Piano spur, and the 2d resumed its attack on Mount Belvedere.

Elements of the 3d Battalion missed direction and ended up attacking the

town of Strinato, but in doing so, captured four heavy enemy mortars, so

the time was well lost. These operations continued through the following

day, with the 3d Battalion finally clearing Colle Piano and moving down

to occupy the valley community of Moritignoso. The 2d Battalion launched

an early morning attack, cleared Belvedere, and moved on to take Altagnana.

In attempting to take Pariana, on the same slope and to the west

of Altagnana, F Co. was met by violent resistance and was forced

to withdraw until the following morning. Supported by mortar fire, the

company then made a coordinated assault, took the town and wiped out the

remainder of the crack Kesseiring Machine

Gun Battalion, which had already been

badly mauled.

Meanwhile the remainder of the 2d Battalion advanced to the Frigido River

line on the 9th. The 3d Battalion advancing abreast and on the left of

the 2d, reached a point two miles from the river after reducing an enemy

position on Colle Tecchione. The 100th remained to garrison the Mount Folgorito—Mount

Belvedere ridge against enemy positions known to be to the east, or regimental

right rear. The advance continued for the next two days with light opposition,

the 100th coming from reserve on the 11th to take over the 3ds place in

the line. The 3d Battalion then swung to the west and entered Carrara,

which had already been partly secured by Partisans.

The Anti-Tank Company established blocks on main roads to the east.

The engineers, trying desperately to keep supply routes open to the advancing

troops, lost four bulldozers, all being blown up by deeply buried demolition

charges.

After consolidating its positions and allowing a little time for supplies

to catch up, the regiment continued the attack on the 13th.

Elements of the 100th Battalion swung toward the coastal sector to make

contact with the 473rd Infantry,

but ran into strong enemy pockets that had been by-passed and a stiff firefight

developed. Meanwhile, the remainder of the battalion assembled in Gragnana,

from where B Company was sent to Castelpoggio to reinforce the 2d Battalion,

which had launched an attack on Mount Pizzacuto.

On 14 April, the resistance in the 100th sector had been cleared only after

a full-scale attack by C Company. Early that morning the enemy launched

a strong attack on Castelpoggio, thinking that only the 2d Battalion

command group was in the town. On being greeted by a hail of fire from

B Company men stationed in strategic buildings, the enemy withdrew in rout

after a fierce fire-fight. An entire enemy battalion was badly mauled in

this abortive attempt to cut off the 2d Battalion. Assault companies of

the 2d then took Mount Pizzacuto at 0900 hours.

| Lieutenant

Daniel Inouye had his right arm shattered by a grenade while elminating

3 machine gun nests. On 14th, Lieutenant Robert

Dole, Company I, 85th Mtn Regiment, 10th Mountain Division, was

wounded in the right arm at Hill 913. In an interview in 2005,

Senator Dole said he ended up in the same hospital as Senator Inouye.

Both men survived after months or operations and rehabilitation and served

as US Senators. |

Our troops were now committed over so wide an area that it was necessary

to call on the 232d Engineers to lay aside their bulldozers and

occupy La Bandita ridge, which dominated the supply route through Castelpoggio.

The engineers relieved I Company in position and held the ridge, successfully

driving off one counterattack. the attack continued, Mount Grugola being

taken by the 2d Battalion while the 100th assisted the 473d

in clearing the town of Ortonovo. The 3d Battalion then relieved the 2d

and pushed on to Mount Tomaggiora and Pulica, where the advance was stopped.

The enemy held this line desperately until the 20th, having heavily organized

this last high ground before Aulla, vital communication center, through

which ran all roads from La Spezia to the Po Valley. On the 20th, the 2d

and 100th Battalions swung to the right of the 3d Battalion to cut Highway

63 and turned west to take Aulla and envelope the resistance holding

up the division advance.

Both battalions ground out a slow costly advance until 23 April, when elements

of the 2d Battalion executed a brilliant flanking movement and seized the

town of San Terenzo. This move resulted in the capture of 115 enemy and

the rout of a greater number. Many of these prisoners were Italian. It

therefore became evident that the Germans were pulling out, leaving their

former ally to hold the sack. This was confirmed when the 3d Battalion

took the strong point at Mount Nebbione the same day and found only a holding

detachment left there.

A task force, composed of Companies B and F, was then formed to exploit

the apparent breakthrough. This force then drove down to seize the high

ground south of Aulla, which fell on the 25th with comparatively little

resistance as the task force and 2d Battalion linked up. For the next two

days as much of the regiment as trucks could be found for followed the

advance of the 473d,

which had exploited the breakthrough and was now driving on Genoa.

Finally, on the 27th, the regiment was ordered to flank Genoa from

the north, seize Busalla, and block the pass at Isola del Cantone

to the north, so as to cut off the enemy’s escape route to Turin. The 100th

immediately moved out on this mission, occupying Busalla at 1000 hours

of the 28th after an all night foot march, inasmuch as it was impossible

to repair bridges in time to get trucks across. Late the same afternoon,

the 3d entered

Genoa, riding commandeered street cars. Elements

of the 3d had also accepted the surrender of a thousand enemy in the hills

directly to the southeast even as Genoa was being entered.

Section

VI

END of THE

WEHRMACHT

The battalion then set up defensive positions to the north and west of

the city, where it remained in occupation until the cessation of hostilities.

On the 29th, the 100th moved into regimental reserve at Boizaneto,

while the 2d passed through its positions and occupied Alessandria, where

it accepted the surrender of over 1,000 enemy from nearby towns. The following

day, the regimental Intelligence and Reconnaissance platoon, with a section

of H Company’s machine guns attached, raced north and entered Turin,

which was held but not entirely subdued by the Partisans.

While this had been going on, by-passed pockets of enemy had outdone each

other in the race to surrender to the Americans. {Turin

is the city where the sacred Shroud of Turin is located.}

At long last, on 2 May {1945},

the end came to the Wehrmacht in Italy. To the once great army that had

fought SO bitterly from Salerno to the Po, that had used every strategem

in the book to delay the inevitable, there were no tricks left; only the

bitter taste of final defeat.

For the men of the Fifth Army,

among them the 442d, the long hard years were over; with victory came the

hope that now, if they were lucky, they might live out their lives in peace,

peace that so many had suffered and died for.

~~~~~

End of Text ~~~~~

|