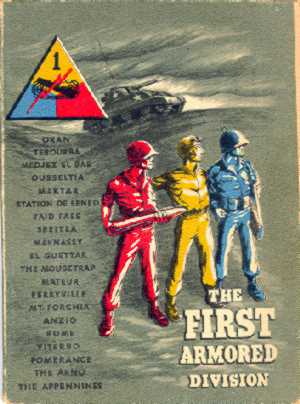

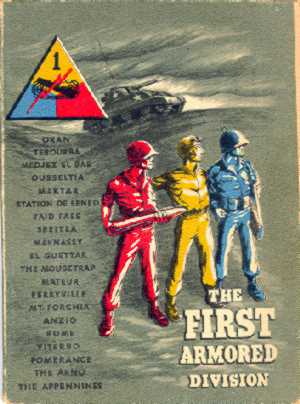

The First Armored Division

You are at: Italian Campaign | First Armored Division

History of the

1st Armored 'Old Ironsides' Division

Based on booklet entitled:

The Story of the

The First Armored Division

This 64-page booklet on the 1st Armored Division was published just after the war ended for distribution to the soldiers and their families. This booklet gives a good overview of the history of the 1st Armored Division. It contains information on places and events without going into specific details. Each page of this booklet contains photos or maps on almost on every other page. The photos are poor quality as the booklet was printed on newsprint. The maps are very simple and includes some cartoon characters. The text covers the activation and the combat in North Africa and Italy.

The only change I made to the text was to combine some paragraphs as many of had only one sentence since the booklet is small format. I've omitted the chapters that did not relate to the Italian Campaign. My comments are in { blue brackets}. See Glossary of Terms at bottom of page.

The Story of the

The First Armored Division

CONTENTS

ACTIVATION

THE NORTH ARFICAN INVASION {Omitted--not part of Italian Campaign}

TUNISIA {Omitted--not part of Italian Campaign}

40,000 GERMANS {Omitted--not part of Italian Campaign}

ITALY {Salerno landing}

ANZIO

THE MOUNTAINS {northern Appenine Mountains}

THE END OF THE WAR {Po Valley Offensive}

THE RECORD

TO SUM UP

ACTIVATION

Some of the German prisoners taken by the 1st Armored Division in the breakout from the Anzio beachhead in May, 1944 got a certain amount of consolation out of the fact that they were captured by "a veteran division", as they put it. Being captured by one of the most experienced American divisions in the theater made their failure to hold the German line a little less disappointing. But despite the 1st Armored's relatively long combat experience, the division was not quite four years old at the time.

The division was organized at Fort Knox, Kentucky, July 15, 1940. It was an experiment in a self-supporting, permanent fighting unit with tanks as the nucleus. This experiment in a self-sustaining blitzkrieg force had never been tried before, and the troops necessary for such an organization were drawn from many army posts.

The two light tank regiments--The 1st and 13th--came from the 7th Cavalry Brigade. The medium tank regiment, the 69th, was formed from a cadre of the 67th Tank Regiment from Fort Benning, Georgia. The 6th Infantry Regiment was lifted intact from Jefferson Barracks, Missouri.

The 81st Reconnaissance Battalion was formed from cavalry troops drawn from two posts. The 16th Armored Engineer Battalion took its personnel from the 47th Engineer Troop and its name from an inactivated World War I unit. The 141st Signal Company was formerly the 47th Signal Troop. The 47th Medical Battalion was formed from the 4th Medical Troops stationed at Fort Knox.

The 68th Armored Field Artillery Battalion was formed from the 68th Field Artillery Regiment, and the 27th Armored Field Artillery Battalion was formed from the 19th and 21st Field Artillery Battalions. The 19th Ordnance and 13th Quartermaster Battalions combined to form the division's Maintenance Battalion.

When the organization was completed, the division had tanks, artillery and infantry in strength. In direct support were tank destroyer, maintenance, medical, supply and engineer battalions. But bringing the division up to its full quota of tanks, guns and vehicles was difficult. Although new equipment was received almost daily, the division had until March 1941, only nine ancient medium tanks. Principal armament of the nine was a 37-millimeter gun.

Fort Knox in 1940 was not unlike other army posts in the nation. There were a few minor differences--the high-crowned overseas cap was worn on the left side of the head, and the few experimental models of the quarter-ton truck that were then on the post were called "peeps" to distinguish them from the command car which had always been called a "jeep" by armored men.

To become expert with their newly-acquired tanks, half-tracks and guns, most of the division attended the Armored Force School at Knox. The students stood reveille at 4 a.m., sat at attention during class and at 4 p.m. rushed to the nearest Post Exchange for a bottle of beer, which helped counteract the hot summer weather.

Everyday some unit attacked from the steel observation tower called 'O.P. Six' to capture some part of a 25 square mile patch of Kentucky brush and gullies. The troops made three-day road marches, scraped and polished their vehicles for Saturday morning inspections, sweated out the lines at the bus station and occasionally dropped by Benny's or Big Nell's, the most easily accessible civilian nightspots.

With more than a year's training behind them, the division left in September 1941, for three month's maneuvers in Louisiana. Living was tough, in some respects tougher than combat turned out to be. The weather was uniformly foul. The night driving was hard on the nerves and dangerous. How necessary the incessant practice was the men did not find out until they reached the plains of Tunisia a year later.

The day before Pearl Harbor, the division was back at Fort Knox. The beds seemed almost too soft for sleeping. The draftees, whom the regular army men had looked on as people only a step above the bugler, had proved themselves as soldiers in the maneuvers. They looked forward to discharges after their year's service. The regular army men expected furloughs.

But war and soldiering had become a serious business. Training took on a new intensity. The division was reorganized, and all tanks, both medium and light were put into two armored regiments, the 1st and 13th. A third armored field artillery battalion, the 91st, was formed, and the 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion was organized and attached to the division.

A few months later, in March 1942, the division was enroute to the Fort Dix, New Jersey, staging area under command of Major-General Orlando Ward. General Ward relieved Major-General Bruce R. Magruder, who had commanded the division since its organization.

It was a "secret" move, but no surprise to the towns people of Washington Court House, Ohio, who had waited four days for the division to arrive. There were movies, food, hot water for shaving and a mammoth banner saying "Welcome First Armored Division" across the main street.

At Dix there were 36 hour passes to New York and motor parks jammed with division vehicles. Nobody knew when or where the division was going, but if was certain this would be no excursion. There would be fighting before long.

The trip was to Ireland, and the division landed in May and June. Training for the next few months was even more rigid and exacting than during the last months in the United States. The men were mentally and physically at their best. The general feeling was one of impatience.

It was toward the end of the training period that Combat Command "B", with about one-half of the division's troops, was alerted to leave Ireland and prepare for an overseas trip to a shore where "…. You'll get off fighting."

Alerted for the invasion were the 1st Battalion of the 1st Armored Regiment, the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 13th Armored Regiment, nearly all the 6th Armored Infantry Regiment, the 27th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, "B" and "C" Companies of the 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion, and detachments of the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion, the Supply Battalion, the Maintenance Battalion, 47th Armored Medical Battalion and the 141st Signal Company.

{In October 1942, the group left Ireland and landed in North Africa where they launched an attack to take Oran, Algeria. The 3rd Battalion of the 6th Armored Infantry Regiment attempted an amphibious landing in the harbor on November 10 but it was a failure. Out of 400 men and 17 officers, only 34 men and 4 officers were fit for duty the next day.}

A Recon man gets his armored

car ready to roll.

Note 1st Armored Div shoulder patch and the

chains on the front tires.

ITALY

Elements of the 27th Armored Field Artillery Battalion and "B" Company of the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion landed at Salerno and Paestum, Italy, with the Fifth Army invasion forces on September 9, 1943.

The 27th first went into action on the night of September 11, a few hours after their 105-millimeter howitzers were unloaded. "B" and "C" Batteries went into direct fire positions covering a vital stream crossing and the following day pulled back to join the third battery in indirect fire positions supporting the 45th Infantry Division. The battalion's guns helped repel the strongest German counterattack of the beachhead on the fourth night after the landing.

Company "B" of the 16th, reinforced by elements of Company "E" took over a bridging mission for VI Corps. They worked north, constructing a bridge every three days, and were joined October 21 by the balance of "E" Company.

The engineers bridged the Sele, Calore and Volturno Rivers. A 270-foot bridge over the Volturno, north of Caserta, was put up in daylight while the Germans conscientiously shelled a bridge site 500 yards downstream. When tie two companies rejoined the division on December 5, they had built 27 bridges for VI Corps.

The 1st Armored Division arrived in Italy in mid-November and bivouacked at Capua, about 30 miles north of Naples. It was learned that the division might be used to exploit a possible breakthrough to the Liri River valley leading from Casssino to Rome.

To get information on the Rapido River, last barrier before the valley, four men and an officer of the 81st Reconnaissance Battalion were sent out on the night of December 13. Deep behind enemy lines the next morning, the patrol took cover in a cave. At darkness they went on, hiding in a haystack by the river as dawn broke. An Italian farmer discovered the patrol during the day, but instead of turning them over to the Germans, agreed to lend one of them civilian clothes so he could make a daylight reconnaissance of the area. That night the patrol started back, and reached the Allied lines on the morning of December 15.

At the end of December Mt. Porchia and a string of small hills across the valley still barred the way to the Rapido. German defenses before Porchia were held grimly, and correspondents wrote in their dispatches that the mountain would be "suicidal" to attack.

Task Force Allen was organized at the end of the year for the purpose of taking the "suicidal" objective. The division's three armored artillery battalions and the tank destroyer battalion, all of which had been firing in support of Fifth Army troops since November 25, were attached to the task force to aid the actual assault on the mountain by the 6th Armored Infantry Regiment.

The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 6th attacked at 1930 hours January 4 {1944}. Heavy resistance slowed the 1st Battalion and the 2nd Battalion was forced to wait. At that moment the Germans blanketed the 2nd Battalion sector with artillery and mortar fire of such devastating accuracy that the troops were forced to withdraw almost to the line of departure. Casualties were heavy.

The next morning the attack was resumed by the 1st and 3rd Battalions. Surging forward through the German minefields, the troops reached the base of the mountain before fanatical resistance stopped the attack at dark. The assault began at dawn and by early afternoon parts of the 1st Battalion were on the mountain. Although there were only 20 men and 2 officers on the peak, they sent back 20 German prisoners. A German counterattack after dark January 6 drove back the 1st Battalion, but by 0300 hours January 7 the armored infantrymen were again on top. The 2nd Battalion was called back into the fight and joined the 1st and 3rd for a final assault on the hill.

By 1100 hours elements of all three battalions were on the crest. A counterattack at 0100 hours January 8 was repulsed and on January 9 the battalions cleared the western slopes. During the night of January 12 the battalions were relieved and returned to the rear. The 1st and 3rd joined the division in a Naples staging area to go on to Anzio and the 2nd stayed in the Porchia sector as part of CC "B".

ANZIO

The 1st Armored Division military police followed the assault waves ashore at Anzio on January 22. They had been sent to expedite the division landings three days later. The Anzio landings were an attempt to outflank the Gustave line on the Cassino front, and the tanks were to be used in a "blitz" role to cut important German road nets to the north.

On January 30 CC "A" attacked. It fought all afternoon and secured the line of departure the division had planned to use for its full-scale attack. Stiffened German resistance and she worst mud since Medjez el Bab kept the 1st Armored tanks on the roads.

The next morning CC "A" attacked again, but their forces were weak, since it had been necessary to lend a medium tank battalion to the British. That day's attack gained 1000 yards and took the tanks beyond the "factory" area on the Albano highway, but there was not enough infantry to occupy the captured ground in strength. The tanks retired to the pine woods, a one-quarter by one mile grove that concealed everything but the fact that it was about the only place on the beachhead to bivouac armor.

It was obvious that if the Germans had anything to say about it, the troops at Anzio were going nowhere. By bringing in every division they could spare from other fronts, the Wehrmacht was able to put the Allies on the defensive. Artillery was brought up and pounded everything in the 90-square-mile beachhead. The Luftwaffe began to come over in more strength than it had shown for months.

The division dug in. Tanks were sunk into the ground until nothing but the turrets showed. The division's trucks looted Anzio and Nettuno for lumber and steel beams for dugout roofs. The only good protection against the personnel bombs dropped by the Luftwaffe was six inches of earth overhead.

On February 16 the Germans, who had been poking at the Allied defenses for weeks, launched a full-scale attack down the Anzio-Albano highway. Division tanks and tank destroyers came to meet them or fired at the Germans from positions already occupied along the front lines. The 1st Armored artillery, which had been in firing positions ever since the day after it landed, kept on firing. By the night of February 18, the German attack had slowed, but it was still a very real threat.

The next morning, with the 6th Armored Infantry Regiment and attached infantry regiment, the 1st Armored attacked up a road leading into the left flank of the German salient Supported by tanks and tank destroyers, the assault rocked the German offensive back on its heels. The slaughter was terrific, but casualties to the 1st Armored troops were comparatively light. The attack finished for good German hopes of driving the beachhead into the sea.

During the next month the division stayed in the pine woods, still in the role of VI Corps reserve. The infantry took over a sector along the Overpass Road on the right of the British for days, and 1st Armored Regiment tanks participated in two limited raids on the German lines.

With the advent of dry weather, "Dust Brings Shellfire" signs began to appear on the roads. It looked as if tanks could be used after all, and during April and May, headquarters began to plan and train for an attack.

The training area used for the tank infantry problems was behind the {1st } Special Service Force front within easy observation the Germans on the mountains east and north of the beachhead, but German shelling of the area was extremely light. Considering the air raids and intermittent artillery fire, going back to the pine woods from the training area was usually looked upon with misgiving.

The division studied two attack plans for the May offense. "Buffalo" and "Grasshopper" plans were similar in most details but the former was aimed at Cisterna while the latter was aimed at Littoria. Artillery positions were dug, reconnaissance was made and assembly areas were selected for both plans. Not until days before the attack did the division know which plan would be used.

For the past two months units left behind. on the southern Italian front had been assembling at Anzio, and the plan called for the use of the entire division, plus an attached infantry regiment, the 135th of the 34th Infantry Division.

When plan "Buffalo" was finally chosen May 21, the division began to move into its forward assembly areas. All that night and day movement in the forward areas was kept carefully hidden.

To keep the Germans from guessing the actual day of the attack, the artillery for the past week had been firing a morning "serenade". It lasted for about a half hour and was fired either at dawn or shortly after, and included practically every gun on the beachhead.

When D-day came on May 23, the usual serenade was fired, but the Germans apparently had come to expect it and thought nothing of it. Then at the tail end of the barrage, the 1st Armored struck at the railroad north of Cisterna and the 3rd Infantry Division attacked the town.

The "snakes", 400~foot long metal tubes of TNT, blew paths through the heavy German minefields and the tanks rolled out. The German defenses cracked wide open before the hundreds of medium tanks thrown into the attack. Behind came the division's infantry and light tanks. By dark CC "A" had gone 1000 yards beyond the railroad and CC "B" had reached the tracks.

Before noon May 24 both combat commands had cut Highway 7 north of Cisterna. Prisoners for the day totaled 850 after the 1st Armored troops had pushed beyond the highway.

The next day's attack put the troops on the slopes of the Albano hills only two miles from Velletri. Plan "Buffalo" had clicked. Some 1st Armored men had been lost. Some of the knocked out tanks could not be repaired, but the damage to the Germans had been disastrous. The 362nd Infantry Division, which had tried to stop the attack, was virtually annihilated.

The sector was turned over to an infantry division and the 1st Armored stuck to the northwest with the 34th Division. The attack was stopped by German resistance in the Albano hill-mass before it had gone more than 2000 yards. The division assembled near Cisterna, and Task Force Howze was detached to aid the 3rd Division attack on Cori and Artena.

May 29 the 1st Armored again went into action, this time on the western slopes of the Albano hills. The attack, headed north to Rome, was stopped until June 3 by the Germans, but broke through and reached the outskirts of the Italian capital the night of June 4.

What may well have been the first American vehicle into the capital

was a 13th Armored Regiment tank from Task Force Howze, which had

struck to the north around the Albano hills and come into Rome from the

East. The "'H" Company tank, headed down Highway 6 with Special Service

Force men riding on the back, reached the city limits of Rome at 0710

hours June 4.

{Click to read the biography of Lt. Roland Luerich, Jr., 16th

Engineer Battalion, who was killed in action on 4 June.}

The 1st Armored, less a few Rome "casualties", pushed beyond the Tiber and took up the pursuit of the badly rattled Germans the morning of June 5. There was some confusion in that morning's attack when an infantry division's artillery, in march column, sailed past CC "B" reconnaissance elements and ran into a German strong-point. CC "A" had some difficulty getting started because a second infantry division discovered it had taken the wrong route and had to counter-march over the combat command's axis.

The 1st Armored men chased the Germans north from Rome to Canino and Viterbo before they ware relieved from the line June 10. They assembled at Lake Bracciano for a rest and a chance to see the city they had helped to capture. Rome was about 30 miles away.

After totaling up the figures, it was found that 1st Armored men had captured 2805 Germans and destroyed or captured 77 tanks, 115 trucks, 50 self-propelled and antitank guns, 17 artillery pieces and 6 armored cars. Losses to the division were only a fraction of the damage inflicted on the Germans.

Distinguishing Insignia of the

81st Armored Reconnaissance Battalion

THE MOUNTAINS

The 1st Armored went back into action at the end of June just north of Grosseto. For the job of pushing the Germans through the rugged coastal mountain; that lay in the sector, enough artillery, infantry and other troops were attached to the division to give it the strength of a young corps.

The left was assigned to CC "B", the center to Task Force Howze and the right to CC "A". On the left and right flanks of the sector the 91st and 81st Reconnaissance Battalions we operating.

A taste of the kind of fighting the division would be called on to do for the next few weeks was encountered by CC "B" as it turned off Route 1 toward Massa on June 22 {1944}. The Massa road was the combat command's main axis, but it passed through a saddle not far from the main highway. Commanding the saddle the Germans had 9 Mark VI Tiger tanks, and they stopped everything CC "B" sent up.

A flanking force was sent back 10 miles and up another road to the east. The Germans were waiting for it and knocked out four TDs and twelve light tanks. There was no road over which the German position could be flanked to the west, but there was a faint trail that led up the ridge not far from the saddle. It was no place to be sending tanks, but tanks were sent, and the Germans withdrew.

The "saddle" action was typical of the fighting throughout mountains. The same flanking action over an almost impassable trail--one the Germans had thought barred anything but a persistent mule--caused Roccastrada to fall in the CC "A" sector.

The Germans contented themselves for the most part with establishing road blocks and destroying roads and bridges before the 1st- Armored tankers. The favorite road block included two Mark VI tanks with their 88 millimeter guns trained on a curve in the twisting road or on some other kind of defile. Since only one or two medium tanks could be used to attack the road block (the terrain limited movement to the narrow roads), the German Tigers usually had to be neutralized by artillery.

In one case in the Task Force Howze sector, however, the 1st Armored troops either killed or captured every German infantryman outposting one roadblock formed by two Mark VI tanks. After that it was simply a question of surprising the German tankers. A medium tank and a TD got the first Tiger after an infantry platoon had worked up to a hill above the roadblock and opened fire with every small arms weapon they had. The second Tiger got away, but was found a few miles up the road with a track damaged.

The mountains got more rugged the farther north the combat commands went, and above Massa CC "B" found itself with 10 miles of hills that had to be covered but which had not even trails.

The infantry dismounted and headed into the hills. They struck fast and surprised a battery of horsedrawn German artillery. They captured the guns and horses intact, and for the next few days supplied themselves by horseback. They scoured their battalion and found a peep driver who had once lived in Texas. He was the chief blacksmith.

Past Castelnuovo the attack was "downhill" to the Cecina River valley which fronted the high peak topped by the fortress town of Volterra. To get to the river on June 30, CC "B" armor took off across country, making the road as they went.

Across the river the armor took up positions astride High 68 which connects Volterra with the coast. Shortly after dark, three Mark IV tanks came east on the highway and reached the outskirts of the 1st Armored tank perk before being discovered. A tank destroyer blasted three-inch AP shells at the exhaust the first and knocked it out. The second Mark IV pulled off the road and sought refuge by a haystack.

But on the other side of the haystack was a medium tank. It pulled forward a few feet, swung the turret and pumped two fast shots into the German tank, then ducked back. The German tank exploded and burned, and the 1st Armored crew had their hands full to keep their own tank from catching fire. The third German crew burned their own tank and escaped into the hills.

Volterra still had not fallen when the division was relieved from the sector June 10, but a battalion of medium tanks stayed behind to assist in the final assault on the town. The reconnaissance battalion, the tank destroyer battalion, the engineer battalion and division artillery also remained in the sector for about two weeks before joining the division at Bolgheri.

At Bolgheri in July the division was reorganized on the table of organization already in effect in most other armored divisions. The two armored regiments were reformed into three separate tank battalions, the 1st, 4th and 13th; the infantry regiment was split into three separate battalions, the 6th, 11th and 14th, and nor changes in personnel and equipment were effected in the artillery, reconnaissance, tank destroyer, engineer, medical and ordnance battalions.

Major General Vernon E. Prichard, who as a Lieutenant Colonel had commanded the 27th Armored Field Artillery Battalion at its activation in 1940, was assigned to the 1st Armored Division as commanding general, relieving General Harmon.

Because reorganization resulted in a reduction of total personnel, the division secured permission to rotate 600 men during the month to the United State. The remainder of the "jobless" were sent to replacement depots. Some later rejoined the 1st Armored and a large number--most of those with more than two years' overseas service--were sent home.

The 1st Armored remained in the vicinity of Bolgheri until assuming command of a defensive sector on the Arno River around Pontedera August 13.

Pontedera was a hot spot. The town was packed to rafters with mines and booby traps, and it bordered the River, which marked the foremost American positions. German machine guns were less than 200 yards away.

When the 47th Armored Medical Battalion learned Pontedera's main hospital was still occupied, the ambulance platoon of "B" Company was ordered to evacuate the 300 aged and invalid Italian patients still in the front-line town. For three days and nights, the ambulance drivers and stretcher bearers worked steadily to remove the civilians. Although the Germans frequently shelled the vehicles as they went to and from the town, only one ambulance was hit. No one was hurt.

While a part of the division held the line, the remainder trained in rear areas. Until the end of August activity along the front was restricted to patrolling. The men swam or waded the river, exchanged shots with the Germans manning the defenses on the north side and swam or waded back. Casualties were light.

On September 1 the division pushed across the river, picking their way through minefields. Altopascio was taken September 4 and Lucca was occupied the same day without opposition. By September 18 the line had moved into the mountains bordering the northern side of the Arno valley. Castelvecchio was occupied and the line held until September 21, when CC "A" troops were relieved and assembled in the Prato-Sesto area north at Florence. CC "B" troops, including tank, infantry and artillery battalions, remained in the line.

CC "B" moved north of Pistoia on Highway 64 October 1. By October 11 the troops had occupied Silla and Porretta. Bombiana fell on October 13 and was held despite German counter-attacks. By October 30 the infantry was beyond Palazzo in an attack on Castelnuovo. Company "B" of the 11th Armored Infantry Battalion took Castellaccio, and CC "B" ordered a defensive line organized.

At 0900 hours October 30 a German battalion attacked the "B" Company position. The company commander called for reinforcements, reported one of the enemy was two yards from him and signed off. Fifteen minutes later he called back and reported the attack repulsed.

The Germans came back again and again in the next four days. They attacked in battalion strength a total of six times in five days but the "B" Company position held. They remained in the line with other CC "B" troops until rejoining the division in November.

During the winter of 1944-45 units of the 1st Armored Division alternated between rest areas and front-line duty. Because the terrain prohibited the use of more than a few tanks at any one time, many of the men in the division, who had been trained for specialized jobs, parked their vehicles and took up rifles and submachine guns to become infantrymen for a while.

THE END OF THE WAR

The final campaign in Italy began for the 1st Armored Division at dawn on April 14, 1945. The German bastion of Vergato fell that day to the 81st Reconnaissance Squadron and the attack was pushed north on Highway 64 toward Bologna. The division fought three days, gaining 10 miles to the north, before being relieved by an infantry division.

Recommitted 10 miles west, on narrow roads and mule trails the division scaled peak after peak before breaking into the fertile flatlands of the Po Valley on April 21. Combat Command "A" reached Highway 9, important lateral valley route, in the early morning and Combat Command "B" at last light had closed up on the left. Prisoners had been trickling into the division cages since the opening day, and the 257 Germans captured on April 21 raised the division's total for the operation to 874.

The hard-pressed German forces fell back before an armored spearhead pushed out by CC "A" on the morning of April 22. By dark the combat command had plunged 25 miles northwest into enemy territory. Modena was bypassed, to the right and left, then cleared by a special force on the following day.

April 22 at 0424 hours CC "A" reached the Po River at Guastalla and consolidated the position. The newly-formed Task Force Howze closed up to the Po about 10 miles west of Guastalla at Brescello. Combat Command "B" had difficulty crossing a river near Modena, but was able to join the rest of the division on April 24.

On April 23 the commander of the new task force organized a small raiding party-initially only a platoon of tanks and 19 infantrymen and set out to the south. The tanks and half-tracks of the party drove past unheeding Germans for miles before firing a shot. Then in the heart of the city of Parma the raiding party began its destruction.

The speed of the maneuver made it impractical to count the destruction, but the tankers and armored infantrymen left the town square littered with dead and wounded Germans and the burning and wrecked vehicles.

Before returning to their base at Brescello, the raiding part drove further west to the Taro River to secure important bridge The raiders' casualties were negligible but hundreds of Germans were killed, wounded and captured.

The entire division had closed up to the Po by April 26. CC "A" crossed the river at San Benedetto and moved into the attack again. The combat command rolled past Mantova that morning, reached a point twelve miles north of the city by early afternoon, and by dark was on the outskirts of Brescia--52 miles from the Po River.

Soon after midnight, reconnaissance elements of the command contacted a German column attempting to escape into Germany. They pulled off the road and waited until the enemy convoy was along side then a medium tank blasted the fourth German vehicle. At that signal everything opened up-armored cars, tanks and machine guns, plus countless rifles and tommy guns. When the fight was over 150 Germans were dead. Some of the 200 prisoners taken reported that a second column was due along the same route at 0500 hours, and the reconnaissance party laid an ambush for it. This time not a German escaped. Those not killed or wounded were taken prisoner, and nearly 50 German vehicles were destroyed.

The Brescia fight had slowed the advance of the armored spearhead, but by dawn it was rolling again. By 0900 hours April 28 the tanks and armored cars were in Coma, and shortly after were on the Swiss border a few miles beyond. Any hope the Germans had of escaping from northwestern Italy was shattered.

CC "B" and the remainder of the 81st Reconnaissance Squadron closed up on the southern flank of CC "A" and set up road-blocks to protect the gains. The Germans, their escape route cut, and their lines of communication and supply severed, surrendered by the thousands. The PW total on April 28 was 12,853. Supply dumps, an evacuation hospital and even a service command headquarters fell to the 1st Armored.

On April 29 the 81st Reconnaissance Squadron moved west, bypassing Milan to the north. As the squadron reached the Ticino River 25 miles west of the city on April 30 the German garrison in northern Italy's greatest city surrendered. The official entry into Milan was led by Combat Command "B" {see photo, below}.

The division rapidly closed up to Vercelli and Novara, threatening the German 75th Corps a few miles to the west. On May 2 at 1845 hours the surrender of all German forces in Italy was negotiated and Combat Command "B" was detailed to administer the disarming of the 30,000 Germans left in the northwestern Italian pocket.

Up to the armistice on May 2 the division's troops--including "service" echelons which had captured a large share of the total--took prisoner 40,886 Germans. Countless quantities of supplies, vehicles, tanks and guns were taken, and 12 German generals were captured. They included the commanders of the 232nd and 334th Infantry Divisions, the chief of staff of the Ligurian Army and the commander of the Lombardy Corps.

In 19 action packed days the division traveled approximately 230 miles from its starting point in Vergato. Some vehicles of the 81st Reconnaissance Squadron, which went an additional 90 miles to Aosta to meet French forces, had as many as 1000 additional miles on their speedometers at the campaign's close.

This last battle was the high point in the division's 30-month combat record--a fitting culmination to three years of overseas service.

A 1st Armored medium tank in

the piazza of Milan's famed cathedral on April 30, 1945.

Note: German car in foreground

and flag waving partisans to left.

THE RECORD

When the two German motorcyclists surrendered to 1st Armored Division tankers in Tunisia in November, 1942, they started a precedent that lasted until the end of the European war. More than 40,000 Germans surrendered to the 1st Armored Division in Africa. More than 45,000 have surrendered in Italy.

German infantry divisions, like the 362nd and the 162nd, have sustained heavy losses trying to stop 1st Armored attacks in Italy. Just one medium tank battalion literally slaughtered elements of the Herman Goering Division above the Anzio beachhead in May 1944, and this instance was only one of many in the Italian and African campaigns.

It is impossible to compute exactly the number of German tanks, guns and vehicles lost to the guns of the 1st Armored Division, but in even the most conservative estimate the figure runs into the thousands.

The success of the 1st Armored Division in 30 months of combat is not due to any one battalion, or to any one arm or service represented by the battalions. The division is a fighting force of tremendous power because all of its 13 battalions have learned the technique of working together smoothly.

There is a natural pride in every man in the record of his battalion. While he will agree that the 1st Armored is the best division in the world, he will not agree that any other battalion, even within the division, is quite as good as his. Fortunately, this rivalry is more or less friendly.

The man from the 1st Tank Battalion can point to the 61 battle streamers on his battalion standard, which was inherited from the original Blackhawks, the 1st Cavalry Regiment activated in 1833. The man from the 13th Tank Battalion, who dates his "It shall be done" motto from the activation of the 13th Cavalry Regiment in 1901, will argue that his unit may be younger but it shoots straighter.

The man from the 4th Tank Battalion, which was activated at division reorganization in July 1944, will probably ignore both arguments because the 4th was made up of veteran tank crews from the 1st and 13th. "Naturally," he might say, "the best was taken from each."

The infantry problem is slightly different. The 6th Armored Infantry Battalion, the former 1st Battalion of the 6th Infantry Regiment, inherited the regimental standard, 34 battle streamers and a 162-year record of continuous service.

The 11th and 14th Armored Infantry Battalions, which had been the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, respectively, of the regiment were changed only in name in July, 1944. They are inclined to comment that while the 6th may be proud of its heritage, two thirds of its World War II record were made by the 11th and 14th, under different names.

Argument among the artillery battalions is generally over which one has fired most of the million rounds of ammunition the three together have shot at the enemy since November 8, 1942.

The 27th Armored Field, Artillery Battalion, which has spent more than 550 days in firing position, has piled up more combat time than any other unit in the division. The battalion has fired 380,115 rounds of 105-millimeter ammunition and 3,447 rounds of 75-millimeter ammunition.

The 68th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, which holds a Presidential Citation for its role in the Faid-Kasserine battles in February, 1943, has fired 379,479 rounds of 105-millimeter ammunition and 5895 rounds of 75-millimeter ammunition.

The 91st Armored Field Artillery Battalion has fired 337,554 rounds of 105-millimeter ammunition and 6000 rounds of 75-millimeter ammunition, but set a unique record in May, 1944, by firing 10,500 rounds at the Germans in 24 hours.

Men of the .81st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron were deprived of their natural opponents in an argument when they incorporated the reconnaissance companies of the tank regiments into their squadron in July, 1944. However, when men from the 81st compare notes on organization with, for instance, a tanker, they usually comment that they have spent as much time behind the enemy lines as the tanker has spent in front.

The 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion is in a similar position in having no one to argue with. The tank destroyers, the table of organization says, do not belong to the division. However, the tankers, who call the 701st soldiers artillerymen, and the artillerymen, who call them tankers, will argue hotly that they are as much 1st Armored as anybody. Whether tankers or artillerymen, the 701st fired 141,064 rounds of ammunition at the enemy up to the end of 1944, and they seldom missed.

The spectacular part of the division's history has usually been written by the units in direct contact with the enemy, but no less important is the role played by the "service" battalions.

The 16th Armored Engineer Battalion led the way in the technique of removing German tank and personnel mines. The engineers were so good at the job that at the close of the Tunisian campaign, they were asked by 5th Army to organize a school to teach other American troops.

They invented a tank-dozer that was adopted officially because it was an improvement over the war department model. They discovered a way to lay a treadway bridge over small gullies by using the crane on the front of a tank recovery vehicle.

They built dozens of devices designed to clear paths through minefields, and used for the first time in combat the 400~foot "snake" to blast a highway through the German minefields that hemmed, the Anzio beachhead. Much of the l6th's work has been done under fire, both artillery and small arms, and more than once the engineers have dropped their tools to fight as infantry.

The 141st Armored Signal Company-which has laid more than 12,000 miles of telephone wire, and issued 42,000 more to the battalions-found out early in the war that a truck was insufficient protection for the operators of its 500-watt radio transmitters. The company mounted its six radio stations in armored half-tracks.

The signal men keep 1400 radios and 400 telephones in working order, maintain a communication net down to battalions and run the message center, which they fondly call the "nerve center" of the division.

While still in the United States, the 47th Armored Medical Battalion began experimenting in field medical aid. The available equipment was inadequate so the battalion invented the surgical truck-a complete operating room mounted on a two and one-half ton truck. So successful was this invention in the Tunisian campaign that it was adopted as standard equipment for all other armored divisions.

In addition to its mobile operating rooms, which can be set up in 15 minutes, and be back on the road in 15 more, the battalion invented a "rolling drug store," a truck which carries a complete stock of medical supplies, and a dental truck capable of doing in the field what had formerly been done only in hospitals.

The 123rd Ordnance Maintenance Battalion can fix anything from the hairspring on a wrist-watch to the tread on a medium tank. The maintenance men work continually to keep the division's 3000 vehicles in running order. When one is worn out or, destroyed, they replace it. So far they have issued 10,000 replacement vehicles.

The guns of the 1st Armored Division--75 millimeter and above--have shot more than 26 million dollars worth of ammunition at the enemy. The battalion's ordnance office issued every one of the 1,960,776 shells used by the guns and the maintenance sections repaired and replaced the guns.

When another battalion of the division designed an improvement in its fighting equipment, the maintenance battalion constructed it. When no parts were available to fix tanks and guns, the battalion made those.

Building roads and bridges, keeping communications open, taking care of the wounded, and repairing guns, truck; and tanks are everyday jobs. They lack glamour. They are hard work. And the 1st Armored Division could have gone nowhere if they had not been done.

The 47th Armored Medical Battalion and the 123rd Ordnance Maintenance Battalion were awarded Meritorious Service Unit Plaques in February 1945.

TO SUM UP

A great many innovations in tactics and equipment were tested on the battlefields of Algeria, Tunisia and Italy by men of the 1st Armored Division. They received some from the United States, invented more to fill a need that did not develop until they had been in combat. The innovations that turned out to be improvements were kept, tested again, and sent back to the United States for use by other armored divisions.

Too, the 1st Armored Division has made mistakes-and everyone was studied and reported to keep other divisions from similar error. The 1st Armored, although it fought brilliantly for two and one-half years, did not participate in the invasion of France or the battle of Germany, but wherever American tanks and half-tracks rolled on French or German soil, there too went the battle lessons that 1st Armored men had died to learn.

In three years of overseas service, the division has consumed 15,000,000 rations. Its vehicles have used 12,000,000 gallons of gasoline.

One man earned a Congressional Medal of Honor. Others have earned 65 Distinguished Service Crosses, 1 Distinguished Service Medal, 74 Legions of Merit, 722 Silver Stars, 21 Soldier's Medals, 908 Bronze Stars, 5498 Purple Hearts and 2231 Combat Infantrymen's Badges. Three men have earned British awards, 26 have earned French awards, 3 have earned Italian awards and 1 man holds a Russian award.

The record speaks for itself. This is a veteran division.

The End

Glossary of Terms

CC "A" - Combat Command A, a combat unit smaller than a Regiment

Task Force Howze - Another combat unit that consisted of elements of 1st Armored Div.

Armored Infantry Regiment - a mechanized infantry unit, not tankers, or the US equivalent of German's Panzer Grenadier.

peep - 1st Armored Division's term for the 1/4-ton truck or what is called a Jeep

jeep - 1st Armored Division's term for a command car

Return to Top of Page.

Return to:The Italian Campaign

Biography of Private James Thompson, Company F, 6th Armored Infantry

Regiment, 1st Armored Division.

Biography of Lt. Roland Luerich, Jr., 16th Armored Engineer Battalion, 1st Armored Division.

Go to Site Map for the entire website and other unit histories.

310th Engineer Battalion of 85th Division

328th Field Artillery Battalion of 85th Division